Wadi Hanifah Cultural Assets

Wadi Hanifah is a lived landscape, shaped as much by people as by water and soil. Life here has always depended on working with extremes rather than resisting them. This project focuses on four buildings at the heart of the valley, designed to reflect and support its cultural life. It follows the same approach—treating the valley not as a backdrop, but as the ground from which architecture naturally grows.

Understanding the Landscape

Located in the heart of Wadi Hanifah, the project sits within a valley that has long acted as a natural artery for life in the region. Stretching over 120 kilometers, the Wadi gathers and channels seasonal rainwater, creating a rare green corridor through the arid landscape. This microclimate has made agriculture, settlement, and trade possible for centuries—long before modern infrastructure arrived.

The site is defined by contrast: dry plateaus and cultivated lowlands, rocky escarpments and fertile soil. The natural conditions are extreme, but full of potential. Summer temperatures reach beyond 45ºC, and flash floods can reshape the terrain overnight. Understanding how people have historically dealt with this climate was essential to our approach.

Building on these lessons, the project avoids nostalgia. Instead, it looks at how vernacular knowledge can be part of a contemporary approach to sustainability and community. Landscape and architecture work together to create a place where cultural heritage is not preserved in isolation, but shared and reactivated.

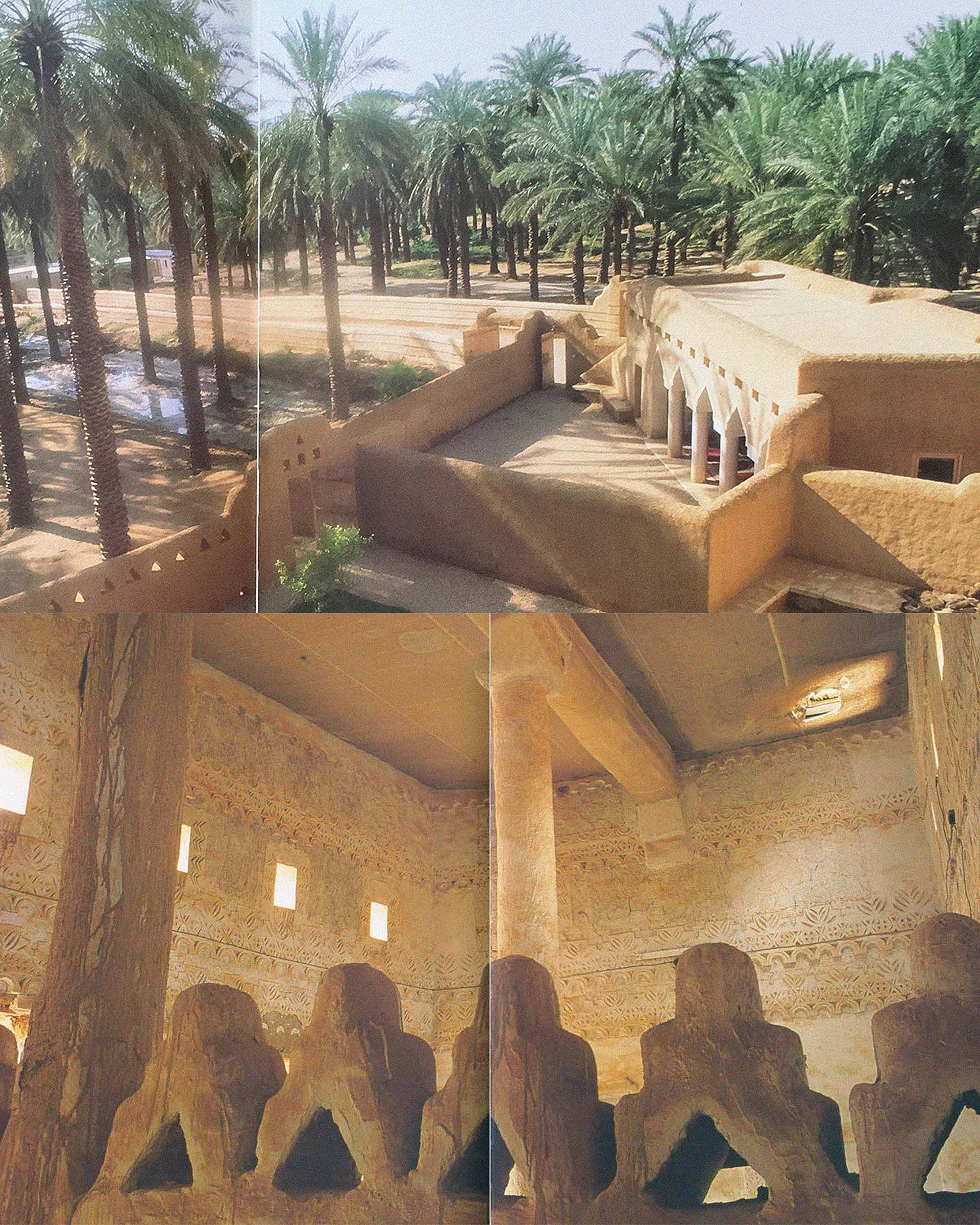

Traditional farm in Diriyah. Unknown source.

A historical photo of Wadi Hanifah in 1917. Unknown source.

Architecture That Belongs

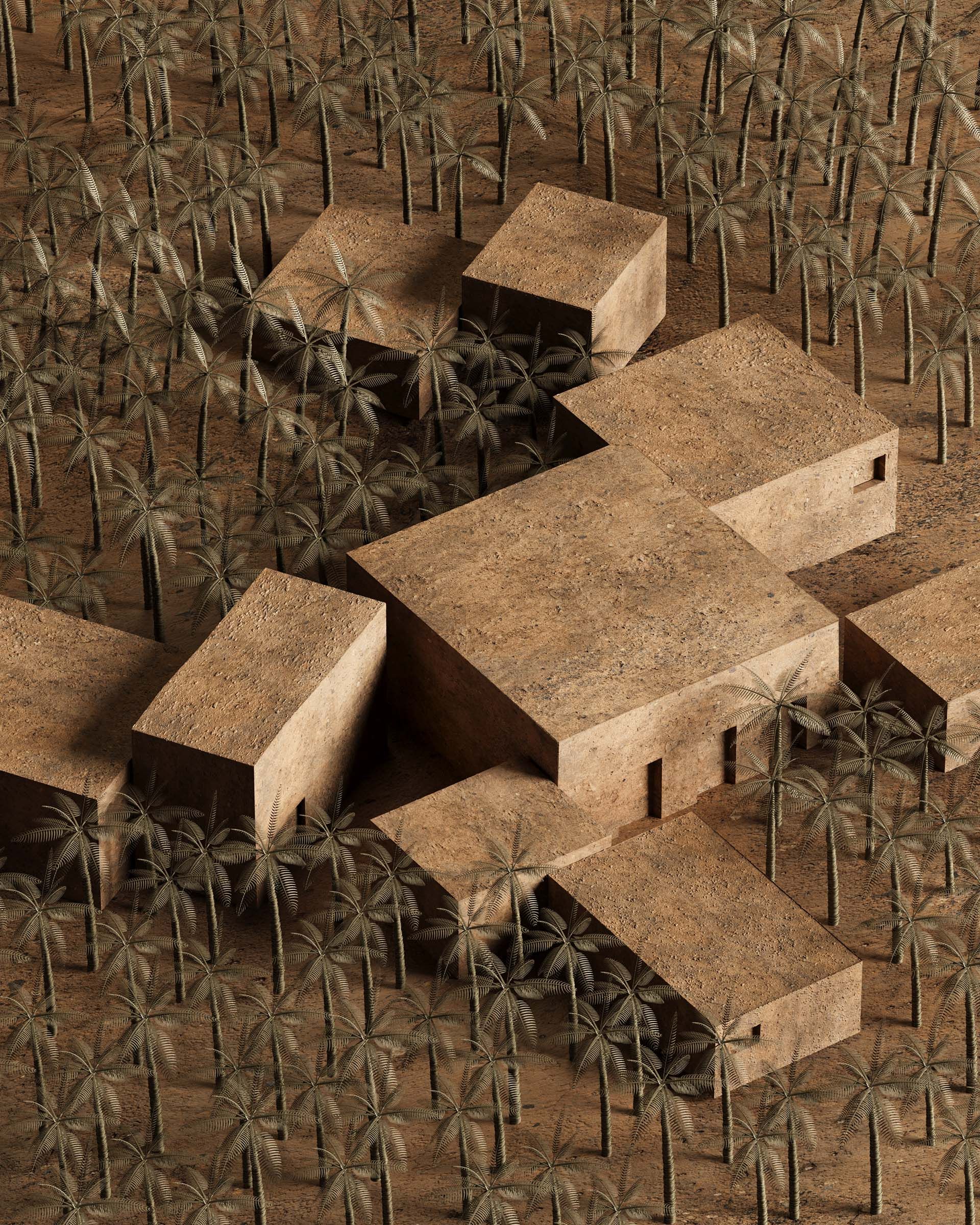

We didn’t start with form—we started by looking at how Najdi rural settlements have long responded to the climate: thick earthen walls to buffer heat, compact layouts that reduce exposure, narrow openings to control light and airflow, and shaded courtyards that create microclimates. These aren’t stylistic references—they’re practical solutions shaped by necessity.

We used mud brick made from local earth for its thermal performance, breathability, and availability. The buildings follow the topography, respecting natural contours and existing vegetation. Water flow, wind direction, and sun exposure all informed orientation and placement. Low perimeter walls define space without closing it off, and construction combines traditional techniques with modern standards.

The result is a climate-adaptive architecture—rooted in local knowledge, built from local material, and shaped by the logic of the Wadi.

General view of the Wadi, 2005. Courtesy of The Globe and Mail.

Rising in the highlands of al-Hissiyah, on the Najd plateau of central Saudi Arabia, Wadi Hanifah runs southeast for around 120 kilometers. The meandering valley ("Wadi" in Arabic) is dry for nearly all of the year, but remains fertile thanks to aquifers close to the surface. It has attracted human settlement for millennia. Centuries before Islam, the tribe known as Banu Hanifah (hanifah means"pure" or "upright" in Arabic) was farming and trading up and down the valley. Extract from "A Wadi Runs Through It" by Matthew Teller.

Building with the Valley

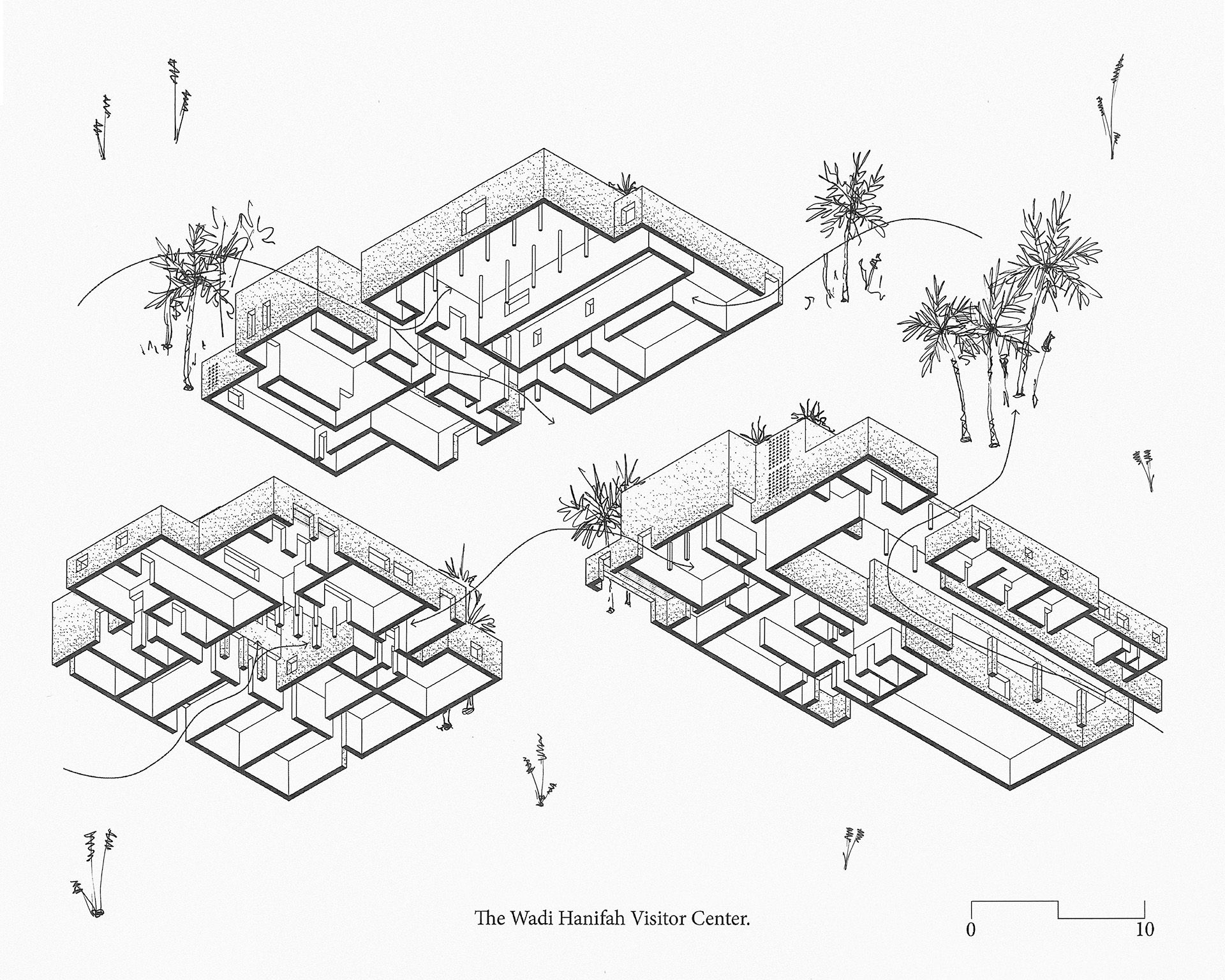

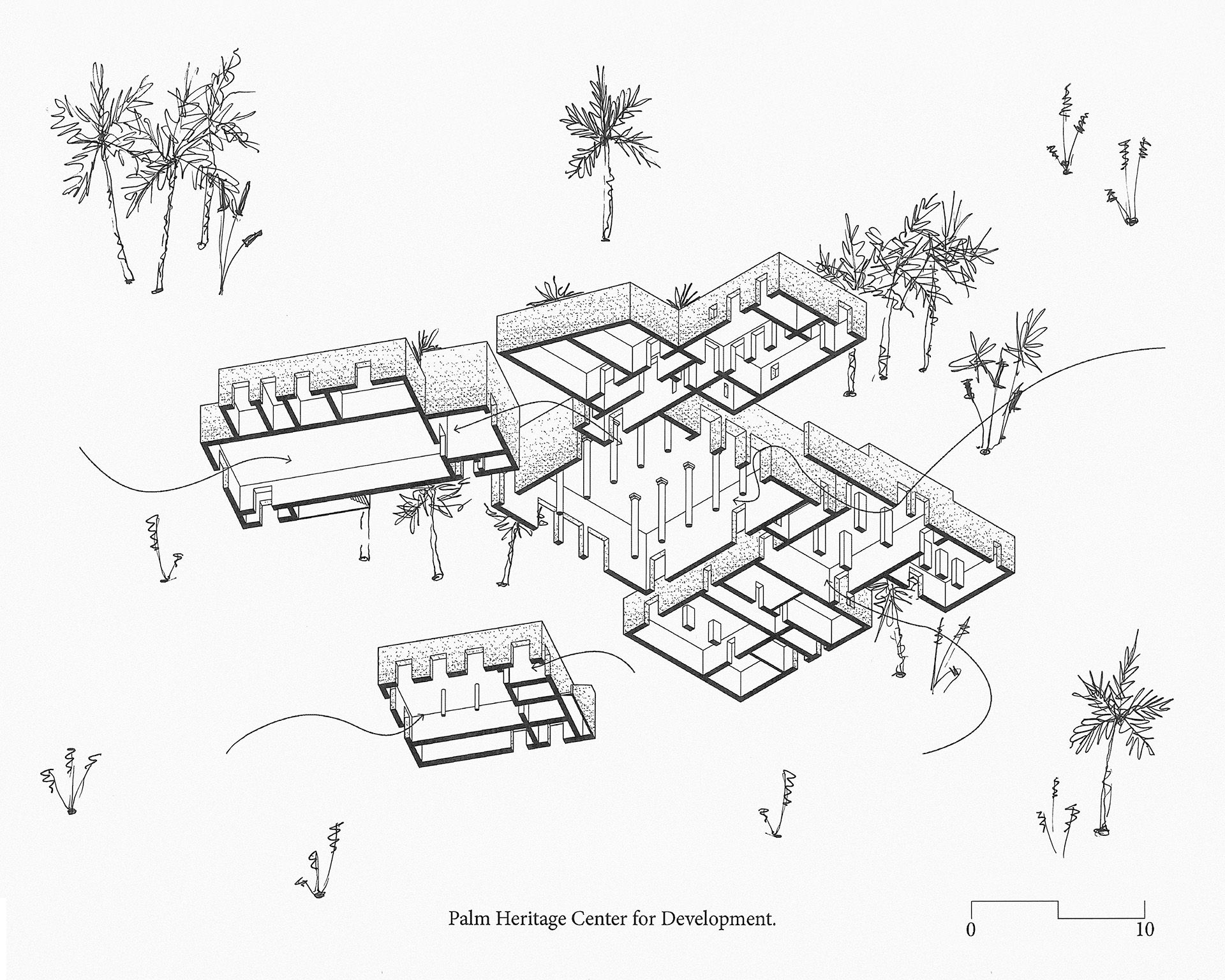

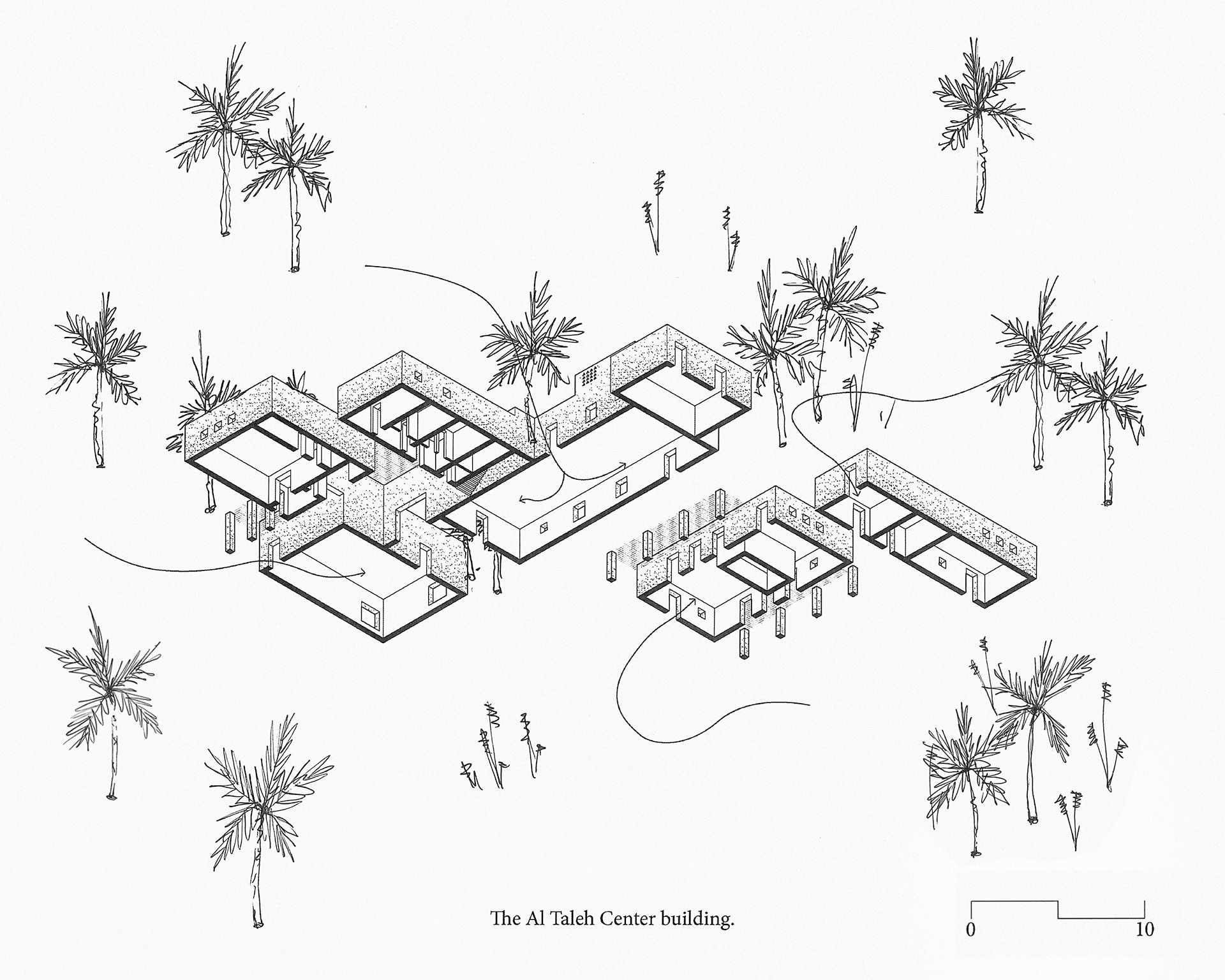

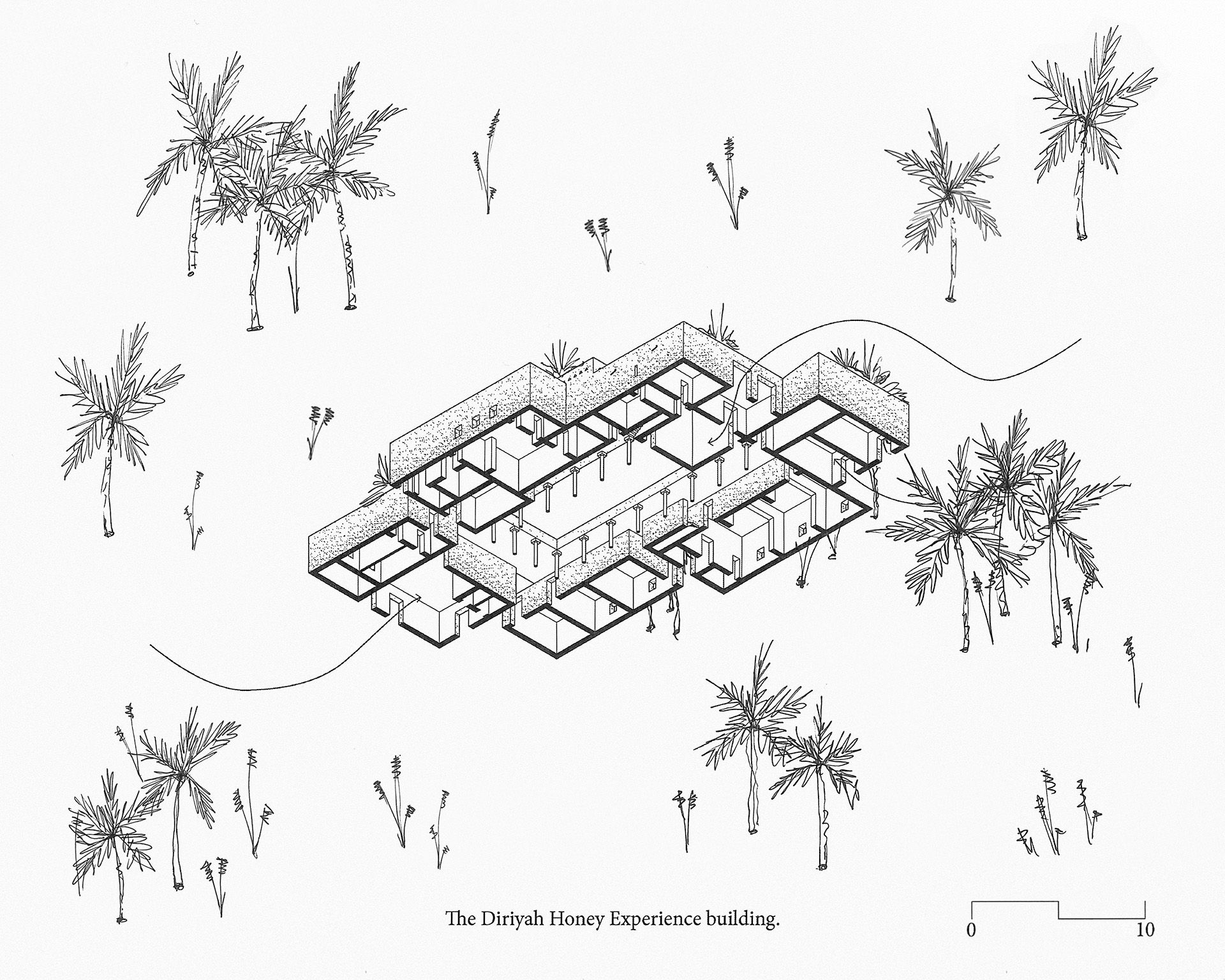

The project includes four pavilions: the Diriyah Honey Experience, the Al Taleh Center, the Wadi Hanifah Visitor Center and the Palm Heritage Center for Development and Research.

Each one is designed for its specific use and location, but they all follow the same logic: respond to the site, stay close to the ground, and connect to each other. A single path links them, so visitors move naturally from one to the next.

We didn’t impose buildings onto the land. We worked with the topography, sun, wind, and water to guide where things go and how they’re oriented. The goal was to make something that feels like it belongs.

The four pavilions are designed as active spaces, not exhibitions. Each one offers hands-on experiences connected to the valley’s culture—whether through traditional farming techniques, apiculture, or the role of the date palm in local life.

The valley’s productivity depends on a careful balance between people and nature. Farmers guide floodwaters, draw from shallow wells, and reuse treated water to sustain crops. Palm groves are tended with drip irrigation, while layered planting—palms above, fruit trees in the middle, vegetables below—creates shade and conserves moisture. In return, communities maintain riverbank vegetation, control pollution, and manage flows, keeping the oasis alive within the desert city.

A Landscape Sustained by People

Wadi Hanifah has stayed productive because of the people who’ve taken care of it. Traditional agricultural practices—date farming, beekeeping, water harvesting—have kept the valley fertile over time. These systems didn’t force the land to change. They adapted to it.

That mindset guided our approach. This isn’t untouched nature—it’s a working landscape shaped by human hands. The project builds on that relationship, treating the land not as a backdrop, but as the starting point.

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Cultural

Private